Action Research Supported by Online Observation

Alice Jackson

Science Teacher, Leysin American School, Switzerland

I consider myself to be a reflective practitioner driven by continuously improving my practice. Although evaluative observations may have their place in schools, their apparent focus on inspection and control of classrooms may not best serve the development of the teacher. I propose that observations are most useful when they support the action research cycle; identify an issue, collect data, and reflect with a colleague to improve my practice and student learning.

One student in one of my science classes was frequently making poor choices. He was disrupting other students’ learning, lacked motivation, and was not making good progress. I felt that I had done everything that I could for this student; I believed that I was being positive, scaffolding appropriately and that I had been imaginative with visual cues and had set consistent expectations. Yet the situation was not improving.

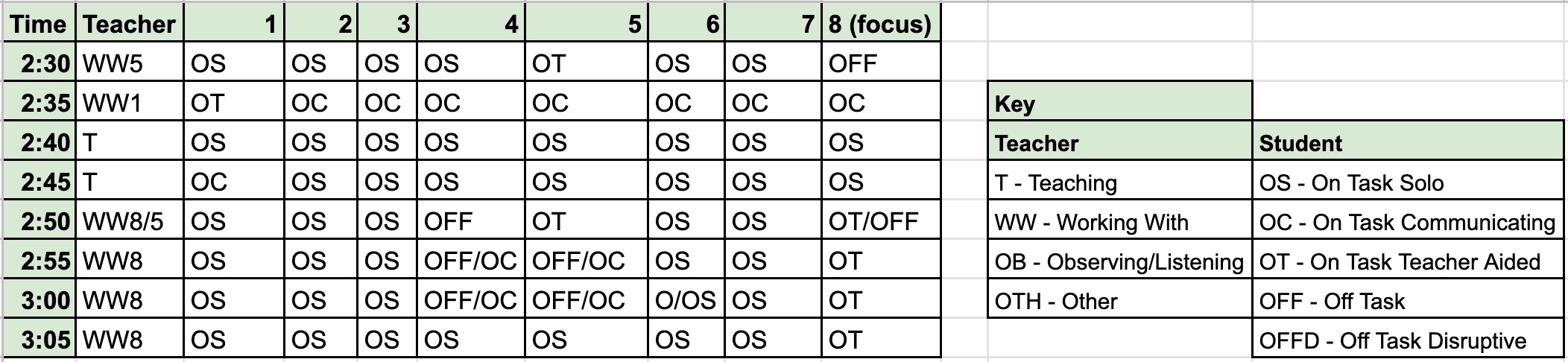

A colleague offered to observe the class, remotely, through Google Meet, to trial a coded observation tool. Together we set a framework for what I would like him to observe: the student’s behaviours, my teacher behaviours, and the behaviours of the seven other students in the class. We agreed that the observer would note his observations every five minutes using a coding system and write any other comments he felt were appropriate throughout the Wednesday afternoon lesson. As part of this pre-observation conference, I shared my goals, the lesson content, and a little background information. It was easy for my colleague to adapt existing data gathering tools and changed the descriptors for our needs.

There were eight points in the lessons where the observer noted the activity of the people in the room. In the majority of observations (fifty-nine of the sixty-four data points) the students were on task, either solo, communicating, or teacher-aided, at no point was anyone observed to be off-task and disruptive. It was cause for reflection that for four of the eight observation points, I was working with the key student. At no point in the lesson was I observed to be simply listening to the students as they worked. The result from reflecting on the data points is that I would like to build the independence and confidence of the focus student to be able to work independently, perhaps with an expert partner, to allow me to distribute my time more equitably.

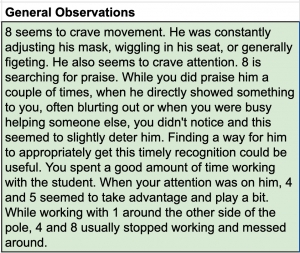

My colleague noticed in his extra comments that the key student was constantly moving and craving praise. While I did give the student praise, he would often blurt out during the lesson that he wanted to show me something. If I was talking to another student and did not give an immediate response, the focus student would feel discouraged and no longer want to share his work or idea, for example cleaning his whiteboard of the correct answer. Finding a way for him to understand that I care about his work and that he is deserving of praise is critical perhaps with a hand for five, an agreed system of showing him my palm to ask him to wait five seconds for me to respond. This will be a challenging task for a student who struggles with their own self-moderation. This non-verbal cue would prevent me from disrupting my conversation with other students and allow me more frequent opportunities to praise the focus student.

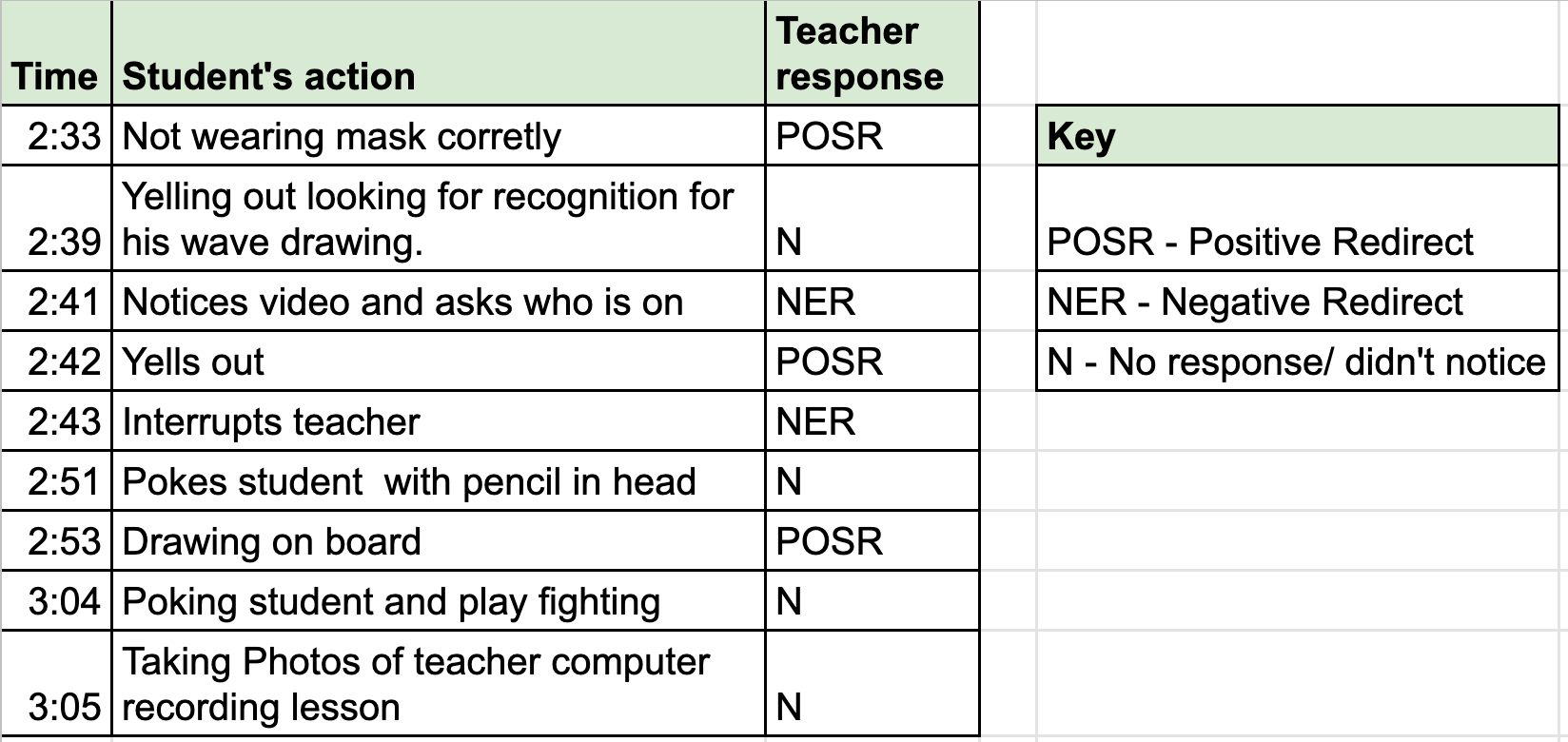

Nine negative choices were observed to be made by the focus student during the lesson. In response to these, I gave a positive redirect in three cases, a negative redirect in two, and chose not to respond or did not see the behaviour in four cases. I found this very surprising, I felt that I had been consistently positive with the student, so this was a really useful reminder to be mindful of my tone. I simply would not have considered this to be an action step with only self-reflection on my practice. I hope that by trialing the hand for five systems, the focus student will have less reason to feel discouraged and likely to make a poor choice and I will have more opportunities to share praise.

Sharing my reflections with my colleague in the post-observation conference I felt empowered to create meaningful action steps, this formative observation tool felt like a move towards a collegiate system with a focus on growth and improvements; a far cry from the evaluative, inspection, and control model which seemed to focus on compliance and supervision.

The success of this peer-to-peer observation structure hinges on two critical ideas. Firstly, the observed teacher must be genuinely open to improving their practice, as I was surprised at the comments that I was given about my negativity, there is a danger that a teacher may not choose their genuine weakness and this type of observation becomes cosy and not developmental. The second critical point is that both colleagues in the partnership must have the ability to formulate helpful criteria for the observation, a consciously (or unconsciously) incompetent new teacher may not develop fastest using this observational style. Accepting these critiques I found that this observation tool supports my own development and reinforces my action research cycle

What do you think about the points raised in this article? We’d love to have your thoughts below.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Alice Jackson is a science teacher at Leysin American School with a physics specialism. She is originally from the United Kingdom and is finishing her fifth year of teaching.

Very important points! Thank you !