Creating a STEAM programme in your international school

Amanda Rose Serrano

Lincoln Community School

How can we as elementary teachers and generalists meet the challenges in our 21st century to help provide students with the skills they need in an ever-changing world?

This is the central question that I have explored for the last few years at Lincoln Community School (LCS) in Ghana as an elementary generalist on a mission.

My Story at Lincoln

Exploring interconnectedness with students and in the elementary school classroom is ideal because I cherish working with a relatively small group of students who I get to know well, while teaching all subjects. So, when I came to Ghana in 2020, the first school year that started in the pandemic, I knew I needed to be flexible – as does international teaching in general. Fortunately, Lincoln is an innovative school with a brand-new elementary school building that is designed with grade level pods where we could create whole new programmes.

“I have a background in the arts & design but I wanted a position as a classroom teacher because at heart, I am a generalist.”

The rooms and spaces at Lincoln are well-equipped for the programmes I was set to create. When you enter a LCS grade-level pod, you step into a huge room called The Hub with flexible seating, furniture, bookshelves on casters, and a projector that casts onto an entire wall. Even greater, both sides of the Hub are lined with windows that provide an unobscured view into four classroom spaces.

In these four spaces, there is a classroom teacher in each – including myself. Two of us are also specialists, I am an art specialist and the other is student support. All fourth grade students and teachers exist in one large group. Roles and duties are subdivided, but done so with a function in mind. This highly flexible grouping allows for new and exciting possibilities.

Given the flexible grouping of students, we as the fourth grade teachers ended up specializing in certain subjects. For me, I was very attracted to the innovation and laboratory approach to teaching and learning. It was exciting to drive my teaching with the design-thinking process, but it was also exhausting in the midst of a pandemic. My first school year was an interactive process where I found myself teaching mainly Math, Art and STEM.

Although I like those subjects, the generalist in me was missing the connections and holistic learning that come with teaching all the subjects. I felt limited and that I was not truly able to teach to my full strengths. Fortunately, the school was preparing to combine the Art and STEM programmes in elementary to become STEAM. Naturally, I was immediately drawn to this idea.

Design and STEAM serve our students in unexpected ways

STEAM prepares students how to approach problems thoughtfully and creatively. It encourages process, failure, resilience, and tenacity. “Fail fast, fail often” is a mantra of the maker movement. STEAM and Design helps students learn critical thinking and problem-solving in a way that nothing else can. It’s hands-on, it’s tangible, it appeals to our kids’ love of technology. Design thinking gives students that flexibility of mind to analyze a problem and come up with creative solutions, consulting with others and testing ideas, finding the best option, refining and implementing it.

While they learn it in Design, STEAM, and in makerspaces at school through building with Lego, perhaps creating an app or video game, woodworking, doing set design for a school production, or puppet-making, the fact is that Design Thinking is perhaps the best preparation we can give our students for the future; how to think creatively, navigate ideas, to try, fail & try again – as these are the skills that will carry our students forward.

Building a STEAM Programmes

STEAM is a new subject at LCS. We have two STEAM Labs, which are a kind of bridge or connecting point between the grade two and three Hubs and another between grade four and five. Our STEAM curriculum was something we chose to build from the ground up. Here, I was entrusted with the freedom to create our curriculum while focusing on making concept-based and ATL (approaches to learning) skill connections, rather than thematic units. This was great because it helped me find deeper learning opportunities, driven by process over product.

My guiding objectives in building the STEAM programmes then became two-fold:

1) Create balanced horizontal programmes for each grade level and a spiraling vertical curriculum from PreK through grade five.

2) Use design methods such as design thinking as a focus, rather than a lot of flashy kits and gadgets.

Planning and creating the curriculum began by defining what we wanted our STEAM programme to offer and how we would build our students’ skills to help them find a bridge to MYP Design. What areas of specialization do we want to offer when STEAM can encompass so much? Knowing that students (and parents) are excited about technology and robotics, I wanted to be sure to include coding and machines and mechanisms. Our students are often encouraged to make things out of recycled materials even in their classrooms so I wanted to include 3D thinking and cardboard. These were areas I especially wanted to spiral up through every grade level.

To get started, I made a spreadsheet with a tab for each grade level. At the beginning of the school year I referenced the school’s Programme of Inquiry (POI) and used that to populate my Working Copy of LCS STEAM Programme sheet. The columns include dates, STEAM unit title, Key Concepts, Related Concepts, the classroom’s Central Idea, and the STEAM Central Idea.

“I made it my goal to create more universal, concept-based central ideas that would be possible for specialists as well as classroom teachers to use to generate their own lines of inquiry, in order to meet content or subject area requirements.”

Next, I had a column to identify which STEAM elements I would be focused on and integrating in the unit (I aim for two per unit in order to keep it manageable and focused for students to make connections). There is another column for STEAM content/skill such as coding, algorithmic thinking, robotics, machines, makerspace, circuits, stop motion, etc. another column for kits or resources I knew we had available at school such as Makey Makey, Snap Circuits, Squishy Circuits, LEGO, WeDo 2.0, Scratch, etc. Finally, my last column was for resources such as books or websites that I might find helpful in developing that particular unit.

Brainstorming at the beginning of the year, I filled out as much as I could using the POI, highlighting the Key Concepts and Related Concepts that would be best for STEAM and tried to identify which unit might be the best for coding, makerspace, etc. for each grade level to ensure that I could start developing a spiraled curriculum. I made notations in the Resources, Kits, and STEAM elements column for anything that came to mind.

Then, I started unit planning using slide decks, which I then linked to the unit title in my spreadsheet. Of course, it has taken consistent work and development over the course of the whole school year to get all the units planned and some of the ideas I had written in my sheet have changed once it came time to design and plan those units in more detail.

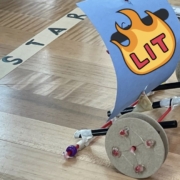

Each unit has at least two items from STEAM identified. For example, our second grade unit about Balance included the E[ngineering] and the A[rt] from STEAM for special focus. We did many explorations giving hands on guided inquiry to learn about the center of mass as well as kinetic sculpture. All of this led up to the students designing and creating Alexander Calder inspired kinetic sculptures.

They learned how to manipulate wire, used hand tools such as pliers and wire cutters, and paper mache techniques in order to transform cardboard and other materials into shapes which they affixed and balanced on their mobile. It was so satisfying to see students let their imaginations take flight and sketch their ideas in their sketchbooks and then learn how to select and use the proper tool to make their project. They became independent, helped each other, and took great pride in their kinetic sculptures, which were displayed in-progress in the STEAM Lab and once completed moved to the elementary school lobby for the whole community to enjoy.

For the second objective, using design methods as a driving factor rather than kits, I felt this was important so that students develop both creative and critical thinking skills. When using kits, I prefer to use them as provocations or a kind of library for students to find out how things work. Students can use kits to further their learning if it helps them ask questions that help them transfer what they learned in order to actually make something themselves. I try to be careful to make the projects in our units open-ended so that when students leave the STEAM Lab they are outfitted with freedom, confidence, and understanding about how things work so they can think of their own ways to be creative and have the skills and knowledge necessary to make things.

Key features of the learning process of my units include; making prototypes, sketching ideas and plans. We use brainstorming, presenting in-progress work, talking about problems and questions with each other and sharing ideas and skills. This can take time, especially when we only have classes for 45 minutes, twice a week. At first, students wanted to do quick projects, something different every time they came to STEAM.

It has been a process to help them readjust their expectations and find the possibilities and satisfaction that comes from this kind of exploration, getting nervous or uncomfortable because their idea seems too hard, and then working through that with their classmates and teachers’ support to stretch and learn what they need in order to achieve what they have set out to do.

Conclusion – My Impressions

My STEAM units have a structure to how they are created, spiraled and communicated to colleagues. They are also underpinned by some fundamental concepts designed to push student thinking, encourage creativity with time dedicated to the design process. During the implementation of these units, we have seen evidence of students changing and growing not only in their understanding, but in the process in which they work and think about problems that they aim to solve.

I have been very fortunate to have such a supportive and well equipped school to build a STEAM programme for. My knowledge of Design Thinking, my efforts in planning and organization have helped me create a solid foundation for the programme. Through my situation and effort, I have managed to create a meaningful and rewarding STEAM programme for LCS.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Amanda is an International educator at Lincoln Community School. With over 10 years of classroom experience, she works on designing learning experiences that inspire students, opening portals and pathways for interdisciplinary connections and transference. She also guides teacher candidates as an instructor and mentor in Moreland University’s Teacher Certification Programme. Connect with her on Twitter @ASerranoEDU.

What do you think about the points raised in this article? We would love to hear what you think below.