Escaping our confines of fear: a call to develop courageous learning communities

Escaping our confines of fear: a call to develop courageous learning communities

Nunana Nyomi

“I’ve been worryin’ that we all live our lives in the confines of fear”, the refrain of Ben Howard’s song, The Fear, kept insistently echoing in my ear. As the song played, I had to put it on repeat as I reflected on the fears I see on display when attempting to further diversity, equity, inclusion, and justice (DEIJ) efforts within my profession of international education. Often these fears are expressed in the form of questions. “What if the students say something controversial?”, “What if our institution goes viral on social media?”, “What if we offend an influential parent?”, “What if we fail?”, “What if…”.

These ‘what ifs’ have become like walls, fencing us in and paralysing us in the face of our responsibility to develop equitable and inclusive communities.

Psychologists say we experience fear in order to protect ourselves from threats. Does this accurately describe the fear that my colleagues and I are experiencing? If so, then we have to take a critical look at ourselves and what we view as threats. If DEIJ efforts are meant to create environments where all can thrive as their full selves, then why do we find it so hard to act? Why do we feel threatened? Perhaps we know, deep down, that taking action requires us to hold ourselves accountable for our part in perpetuating and benefiting from inequities in our communities. Perhaps we worry that standing up for justice may cost us the relatively modest trappings we have worked so hard to obtain. This zero-sum thinking blinds us from the cost of our inaction.

The cost of our fear

The opportunity cost of maintaining our status quo is a misguided generation of students within our care. According to ISC Research, our international schools now serve a much more diverse population than the Western expatriates many were originally designed to serve. However, our curricula are still largely dominated by eurocentrist perspectives, our teachers and leaders are mostly white and western, and many of our schools still serve a narrow group of wealthy elites. Yet, many of our mission statements proudly proclaim that we are developing internationally-minded global citizens. Our empty statements and shallow focus on food, flags, and festivals, are not enough to prepare our students to engage with our dynamic world.

We have a tremendous responsibility to get past our inhibitions and act now. All we have to do is watch our daily news headlines to notice the growing trend that we live in an increasingly polarized world which is facing looming existential threats. Climate change, military conflicts, and the resulting mass migration which we are already witnessing are all potential harbingers of what is to come. Furthermore, some in our care face daily abuse and discrimination due to their race, sexuality, ability, and other forms of identity. We fail our most vulnerable students and staff when we remain too afraid to explicitly address the harm they experience. Given the urgency of our challenges, we must ensure that this generation of students can feel seen and can develop the agency necessary to bridge differences in order to address our world’s problems. How might we break out of our fearful funk to create more inclusive and equitable communities to address these challenges?

My quest for strategies to address our fear-based crisis of inaction led me to borrow from the field of psychology, where strategies abound to help individuals overcome emotions of fear. While the semantics might be different, there are many DEIJ strategies that are very similar in approach to the world of psychology. Therefore, psychology provides another potential access point for DEIJ concepts. Just as there has been greater acceptance of therapy as important for wellbeing, I believe we are in need of therapeutic approaches to transform ourselves and our communities to become places of flourishing. In my own exploration, I came across two of these strategies which can be adapted to our contexts as international educators: cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) and exposure therapy.

Borrowing from Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT)

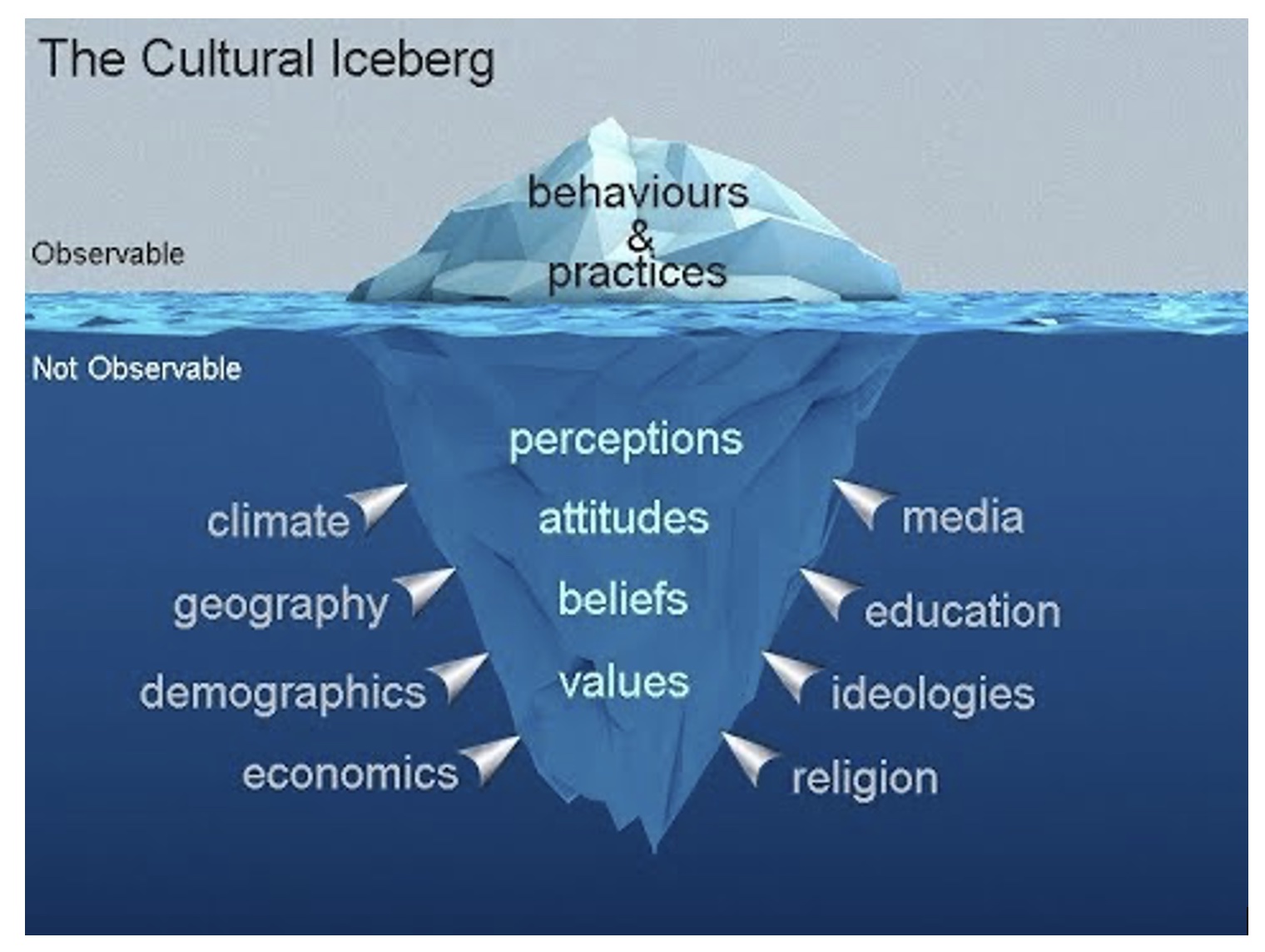

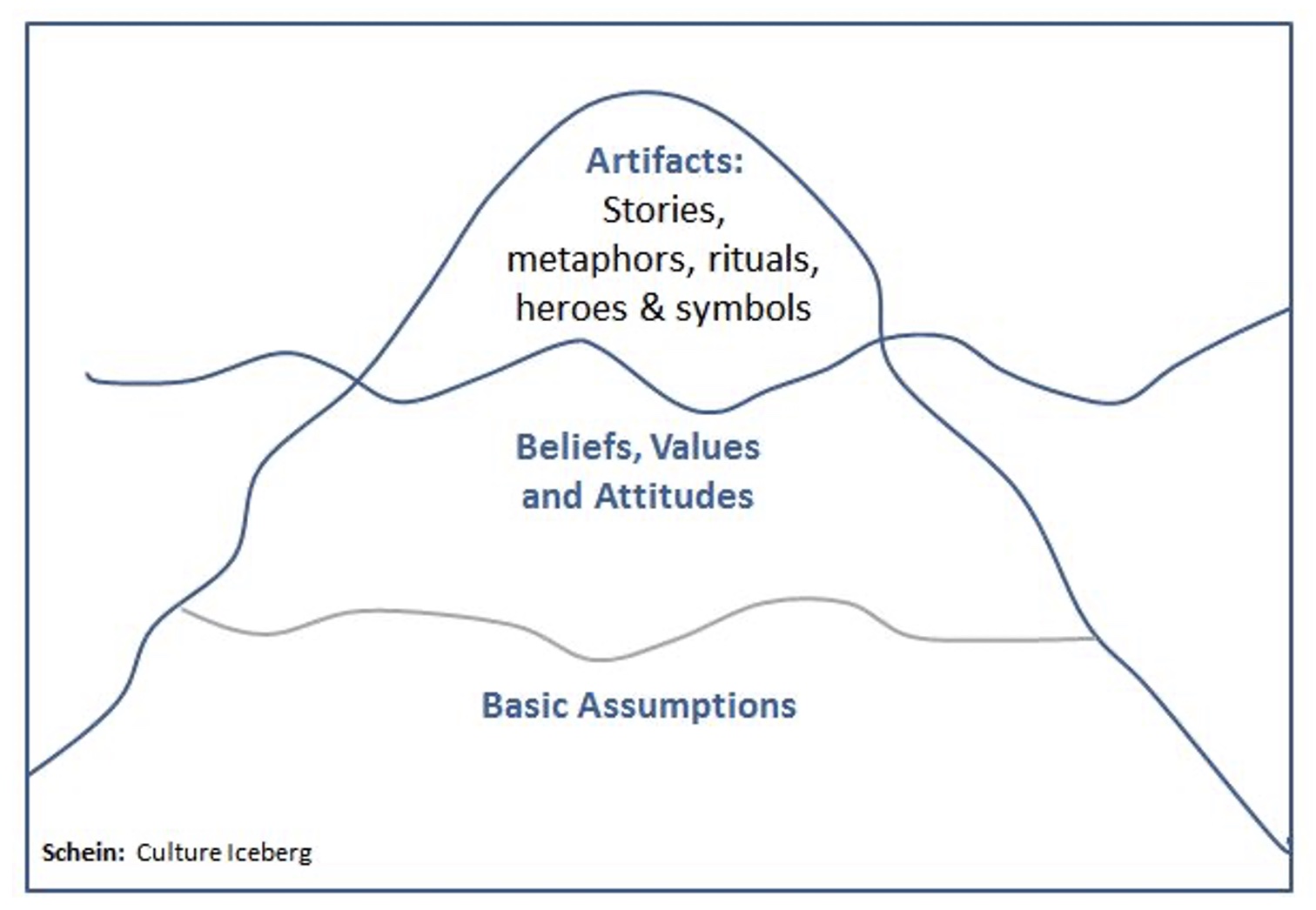

CBT was developed to help individuals conquer unhelpful ways of thinking that can lead to psychological distress. One of the CBT strategies is to address the underlying beliefs that impact the emotional responses we have. Often, the cause of our fears can be found in irrational beliefs or expectations of ourselves. For example, in our largely white-western educational cultures, perfectionism has become an intoxicating drug. We are always striving to do more, be better, and push ourselves to never fail, because we have been socialised to falsely accept flawless performance as the standard. Whether it is perfectionism, eurocentrism, ableist thinking, heteronormativity, or something else that afflicts us, we have to be introspective about the beliefs that underpin our unwillingness to take action.

CBT can interrupt the negative spirals of ‘what if’ thinking that often halts DEIJ work. This therapy invites us to challenge our idiosyncratic beliefs by teaching us that we are worthy of self-acceptance when we struggle or make mistakes; that others are worthy of acceptance even when they behave differently to what we may expect; and that sometimes life has challenges but that does not mean that we are facing utter disaster. This shift away from perfectionism and other irrational beliefs makes room for the diverse perspectives that we find in our international communities. Thus, allowing us to build up the courage we need to truly give voice to the voiceless, even if it may mean opening ourselves up to criticism. From this courageous stance, free from irrational beliefs, we can make positive changes towards equity and inclusion.

Exposure Therapy Strategies

As the name suggests, exposure therapy aims to desensitise individuals from their fears by having them confront them in a safe environment. This can be done through a variety of methods from having individuals use their imagination, using virtual reality, or using live confrontation. Admittedly, exposure therapy is not without its critics. It could potentially induce more anxiety or trauma to expose an individual to their fears. However, when it comes to nurturing a diverse, equitable, and inclusive international education community, it is vital that we expose ourselves to individuals and perspectives which we may fear. How often do we cultivate friendships with those from different races, nationalities, abilities, religions, gender identities, or sexual orientations to ourselves? How much literature do we read from non-dominant perspectives? Do we ever make an effort to de-centre ourselves and listen to those who are traditionally unheard in our communities? We cannot do equity and inclusion work if we are not reaching out to form these relationships or hear their perspectives.

Now, before everyone rushes off to find that one BIPOC friend or attend that one cultural festival, I must clarify that we should not fall into the superficial and tokenising equity traps. Rather, I am suggesting that we must engage in deep and meaningful work to embed and centre a broader range of perspectives in our communities. As educators, beyond forming friendships across differences, this means learning to employ culturally relevant pedagogy strategies and consistently immersing ourselves in literature to enrich our understanding of student experiences such as Dr. Danau Tanu’s Growing Up in Transit. We need to truly expose ourselves to difference in order to overcome the fears that paralyse us.

The choice we have to make

While CBT and exposure therapies tend to be applied to individuals, I would argue that our learning organisations are in need of collective therapy. Just as with any other therapy, this will take more than a one-time workshop to address. Our institutions and their leaders must ensure that adequate time and resources are provided to move past our fearful inertia. We must commit to and invest in advancing DEIJ initiatives so that everyone feels a true sense of belonging at our institutions.

Strategies which root out our fears are essential for us to make progress in disrupting the status quo in the manner that DEIJ work requires. After all, we are collections of individuals with anxieties and fears, these fears creep into our decision-making. As we mould the next generation to tackle the urgent problems we see in our world, and as we aim to protect the most marginalised individuals in our community, we cannot afford to let our fears paralyse us into inaction. Are we prepared to work on ourselves and our institutions to break through our fears in order to build a more equitable world, or are we prepared to inherit a more polarised and inequitable world? Let’s be courageous and choose the former.

“…I will become what I deserve…” Ben Howard’s voice echoes repeatedly as the bridge of the song The Fear builds to a crescendo. When it comes to DEIJ, if we continue to live our lives in the confines of fear, we will only have ourselves to blame for what our institutions will become in the face of the challenges that face us.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Nunana Nyomi is the University Advisor and DEIJ Coordinator at Leysin American School, Switzerland. Nunana is passionate about developing communities where everyone can thrive as their full selves and helping students find career pathways which allow them to fulfill their potential. Nunana currently serves as University Advisor and DEIJ Coordinator at Leysin American School (LAS) in Switzerland.

Prior to joining LAS, Nunana was based in the Netherlands as Associate Director of Higher Education Services for the Council of International Schools (CIS) and provided programs to support student transitions from school to university education. Additionally, Nunana served on the CIS Global Citizenship Team and on a special CIS Board Committee on Inclusion through Diversity, Equity, and Anti-Racism (I-DEA). He also previously led international student admissions for Calvin University in the U.S. Nunana is a Third-Culture Kid who grew up in the U.S., Ghana, Kenya, Switzerland, and the U.K. He has a BA in International Relations and French (Calvin University) and a MA in Higher, Adult, and Lifelong Education (Michigan State University).