Dr. Yael Cass

Director of School Operations Services at International Schools Services

In the vibrant ecosystem of our international schools, every individual plays a pivotal role. As leaders, we often endeavor to understand the heartbeat of our school’s culture. We seek feedback, we organize workshops, and we initiate dialogues. Yet, despite these proactive measures, there remain unspoken sentiments and silent gaps between lived experiences and our understanding.

Drawing from years of diverse engagement in the international educational sector, I’ve come to recognize a recurring disconnect between leadership perceptions and ground-level realities. This isn’t just an academic observation; it’s a lived experience that spans the entire educational ecosystem. My roles as a customer (full-paying parent), board member, and school administrator with a research background on the efficiency of governance in international schools have provided me with a comprehensive understanding of these complexities. My consultancy work has further deepened this understanding, revealing the often-underestimated value of the role of operations and support-staff in achieving a good organizational culture and assisting schools to achieve their educational excellence goals.

It’s important to note that the isolation of leadership is often a circumstance, not a choice. School heads may find themselves in positions where they are not fully exposed to the lived experiences of their staff. This is not to blame them, but rather to highlight the systemic issues that can prevent open dialogue. Employees, whether due to fear, respect, or a combination of both, may hesitate to voice critical feedback, perpetuating a culture of inequity and inefficiency.

Further complicating this landscape is the perspective of our support staff, especially those from diverse industries and corporate backgrounds. While they bring a wealth of experience, they often grapple with aligning the proclaimed ethos of education with observable practices. This disconnect can be glaring, as they sometimes find themselves questioning the correspondence between our stated objectives and our actions. On the flip side, educators, deeply immersed in their specialized environment, might inadvertently overlook these disparities. Their profound dedication to the educational realm can sometimes create blind spots, making it challenging to recognize what might be evident to those from different professional landscapes.

Therefore, it’s imperative to bridge these multiple gaps between perception and lived reality. We must acknowledge the vital role that each cog in the educational wheel plays in shaping our students’ future, and creating channels for open, fearless communication across all levels of our educational institutions.

As we strive to align perception with lived experience and foster a more equitable school culture, let’s explore some actionable strategies that can serve as catalysts for meaningful change.

Tailored Onboarding: Immersing Support Staff in the Educational Mission and Vision

Support staff in educational institutions often come from a variety of industries, bringing with them a wealth of experience but potentially lacking familiarity with the unique landscape of education. To bridge this gap, a well-crafted onboarding process is indispensable. This should go beyond mere orientations and delve into the intricacies of the educational system, including accreditation standards, curriculum frameworks, and even a day in the life of a teacher. A glossary of educational jargon can also be invaluable for those new to the sector.

Drawing from my extensive experience leading global communities of HR and operations professionals in international schools, I’ve observed that these professionals often express initial reservations about transitioning into an educational setting. The pace, practices, procedures, and structure may be quite different from the corporate world to which they may be accustomed; however, the demand for high service standards, especially from premium educational institutions, remains constant.

However, onboarding is merely the initial step in a continuous journey of alignment and immersion. The objective is not just to inform but to integrate support staff into the educational ethos of the institution. This often-neglected aspect can lead to a disconnect between educational goals and operational objectives. Research in organizational behavior underscores the importance of alignment: when an employee’s values and skills are in sync with their work environment, it enhances their commitment, motivation, and overall job satisfaction.

To sustain this alignment, schools should consider implementing ongoing educational sessions, regular check-ins, and cross-departmental meetings that feature case studies relevant to both educational and operational roles. These initiatives serve a dual purpose: they not only keep support staff updated but also ensure that they are culturally and philosophically aligned with the school’s mission and vision.

Anonymous Feedback Channels: Culturally Sensitive Mechanisms for Genuine Insights

In many countries, cultural norms and historical experiences can inhibit open and candid feedback. Direct criticism might be perceived as disrespectful or unkind, and voicing concerns about institutional practices or leadership could be misconstrued as ingratitude. This presents a unique challenge for educational institutions aiming to gain authentic insights into their organizational culture. To circumvent these hurdles, the implementation of anonymous feedback channels, such as carefully designed surveys, becomes essential.

The cornerstone of an effective anonymous feedback mechanism is cultural sensitivity. Survey questions should be meticulously crafted to honor the cultural norms and historical nuances of the host country. This ensures that the survey is not only respectful but also effective in eliciting genuine responses. To achieve this, assembling a diverse design team is imperative. The team should mirror the heterogeneity of your staff, encompassing various departments, roles, and cultural backgrounds.

Creating a survey that garners honest feedback is a complex task. The questions must align with the school’s overarching goals while also being sensitive to cultural norms. For instance, rather than asking a direct question like, “Do you think leadership is effective?”, a more nuanced and culturally sensitive question could be, “How comfortable do you feel with the current leadership style?” This approach ensures that the survey yields information directly pertinent to the school’s objectives and the enhancement of its culture.

Before deploying the survey to the entire staff, it’s advisable to conduct a pilot test with a smaller, diverse subset of employees. This allows for an assessment of the survey’s effectiveness and cultural appropriateness, providing an opportunity for necessary adjustments.

By adopting these comprehensive measures, educational institutions can establish anonymous feedback channels that are both respectful of cultural and emotional sensitivities and effective in providing invaluable insights. The insights from the surveys can serve as a tool to foster conversations within diverse focus groups, or through confidential interviews facilitated by external consultants. These opportunities increase the opportunities for open discussion and honest feedback. The results can serve as a roadmap for meaningful organizational changes, contributing to a more cohesive and effective educational environment.

Empathy Workshops

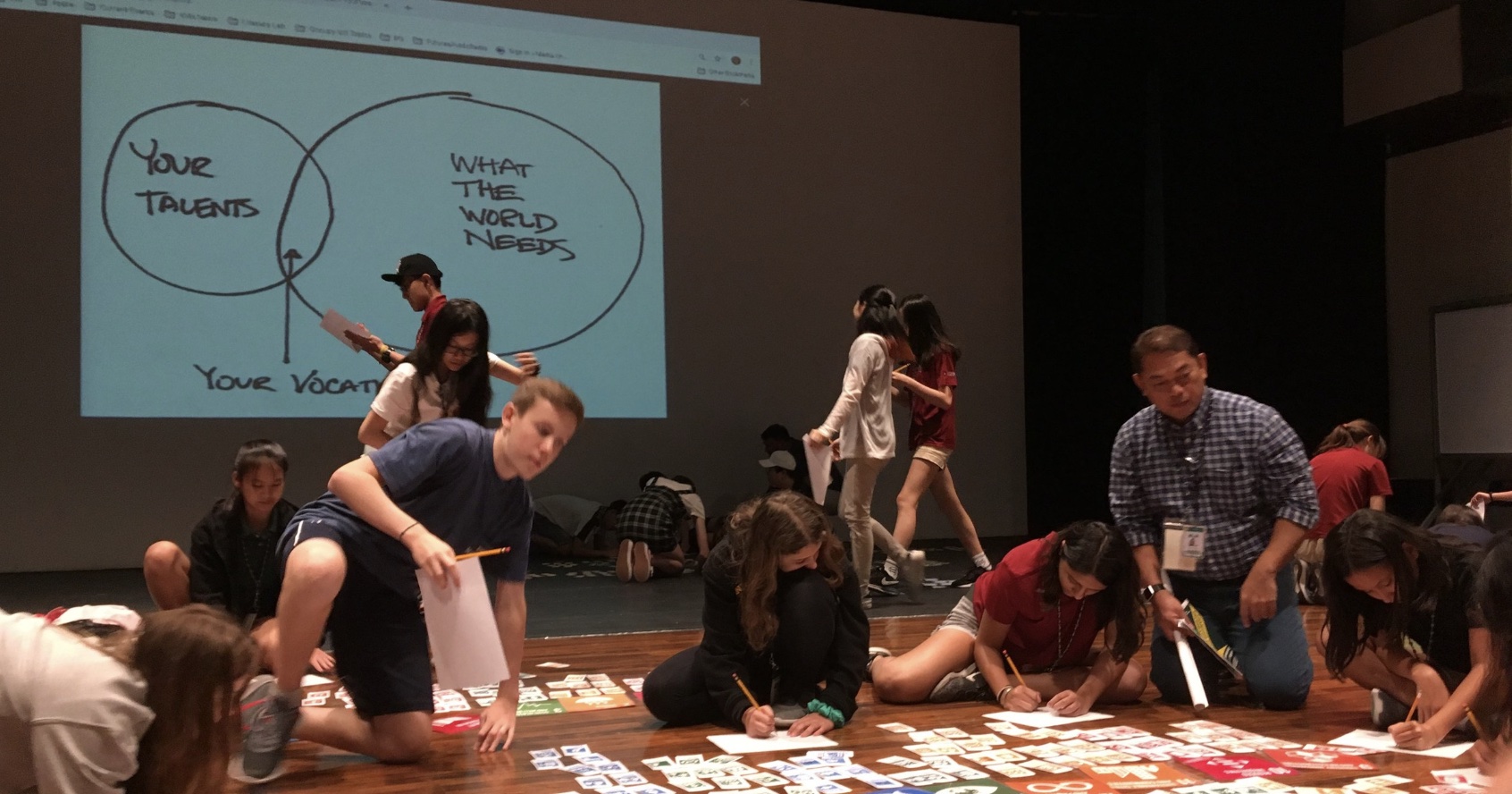

Empathy Workshops can serve as a cornerstone for fostering a more cohesive and understanding work environment. This is particularly relevant in educational settings, where staff roles and responsibilities can vary significantly. The workshops aim to cultivate empathy among all staff members, from educators and support staff to leadership. The overarching objective is to nurture a culture in which each individual can comprehend and appreciate the unique challenges and contributions of their colleagues, thereby enhancing teamwork and minimizing friction.

Various techniques are employed in Empathy Workshops to achieve this goal. Storytelling is an effective approach. Staff members share personal experiences related to their work, effectively breaking down stereotypes and assumptions. For example, a support staff member might discuss the logistical hurdles of organizing a school event, while a teacher could delve into the emotional challenges of managing a difficult classroom. Hearing these stories firsthand fosters a deeper level of understanding and respect among staff members.

Role-playing exercises are another way to enable participants to step into their colleagues’ shoes and experience the challenges they encounter daily. For instance, a teacher might role-play as a janitorial staff member, or an administrator could assume the role of a classroom teacher. These exercises are eye-opening, revealing the complexities and demands associated with different roles within the organization.

Interactive discussions and group activities can further explore the concept of empathy, discussing its significance in effective communication, conflict resolution, and even its impact on students’ educational outcomes.

Anonymous Internal 360-Degree Climate Surveys

Anonymous internal 360-degree climate surveys can serve as transformative tools by offering a comprehensive view of internal dynamics that might otherwise remain hidden. In environments where support staff and educators often operate in separate silos, these surveys facilitate cross-functional feedback, allowing both groups to offer insights into each other’s performance as well as that of their supervisors. This is particularly vital in educational settings where internal politics can obscure objective assessments and decision-making.

Leaders, often removed from the day-to-day interactions of their teams, may find it challenging to accurately gauge the organizational climate. A meticulously designed 360-degree survey can act as a potent mechanism to navigate these internal complexities. By incorporating leading questions that elicit specific viewpoints, such surveys can convert hallway politics into constructive dialogues. For instance, instead of a vague question like, “Are you satisfied with your team?”, a more targeted question could be, “How effectively do you think your team collaborates on project-based tasks?” This approach not only yields a nuanced understanding but also generates actionable insights.

I’ve observed that a well-executed 360-degree survey can unveil hidden tensions between departments or even within teams, affecting project outcomes. For example, educators in one case felt that the support staff were not adequately responsive to their needs, while the support staff believed that the educators failed to appreciate the logistical challenges they encountered. The survey’s findings led to a series of cross-departmental meetings that significantly improved communication and collaboration, benefiting the entire organization.

By utilizing anonymous 360-degree surveys, educational institutions can transcend the constraints of internal politics and isolated leadership perspectives. They can cultivate an environment where feedback is not merely encouraged but is also constructive and actionable, thereby facilitating meaningful organizational improvements.

Engaging External Consultants: A Unique Advantage

The engagement of external consultants offers a unique advantage: an unbiased, external perspective capable of cutting through internal politics and preconceived notions. This neutrality fosters a more open dialogue among staff members, who may feel more at ease sharing their genuine feelings and observations without the fear of retribution.

In my capacity as Director for School Operations Services, I conducted many organizational development consulting and operational audits to international schools across the globe. My external viewpoint has proven invaluable for eliciting candid, constructive feedback. For example, during one consulting engagement with a small school, the external evaluation unearthed a deeply troubling issue of which the school’s leadership was entirely unaware. The staff perceived that the leadership was either indifferent to the situation or, worse, supportive of the unethical behavior in question. The confidentiality and security of the external evaluation process encouraged staff to openly discuss these sensitive issues. This revelation was a watershed moment for the school’s leadership, who had been oblivious to the problem. Armed with this newfound knowledge, they took immediate action to rectify the unethical behavior and instituted policies to prevent similar incidents in the future. This significantly improved the school’s culture as well as its operational effectiveness.

The safety and well-being of employees are paramount throughout this process. Confidentiality is rigorously upheld, and feedback is presented in a manner that safeguards individual identities, ensuring that employees feel secure throughout the process.

By leveraging the impartial expertise of external consultants and prioritizing employee safety, school leaders can acquire a comprehensive understanding of their institution’s culture. This approach not only identifies areas for improvement but also yields actionable insights for creating a more cohesive and effective educational environment. Importantly, it does so while safeguarding the well-being of the school’s most valuable asset—its staff.

In the intricate tapestry of international school ecosystems, every thread—be it an educator, a support staff member, or a leader—holds unique importance. While we strive to weave a harmonious pattern, it’s essential to remember that the fabric is ever-changing, influenced by the individual experiences and perspectives of its constituents. It’s not enough to merely understand or appreciate these threads. We must actively engage with them, continually reassess, and realign our strategies to ensure a cohesive, effective, and nurturing educational environment. The journey towards this ideal may be complex, but it is one that holds the promise of profound impact, not just for those within the school walls, but for the broader community and, most importantly, for the generations we are shaping.

About the author

With over 20 years of experience in leadership, management, and operations, Dr. Yael Cass is a seasoned professional in organizational development, management, and operations. She offers consultancy services in a variety of areas, including organizational development, culture, HR strategies, innovation, and business and capital development.

Her unique lived experiences as a full-paying parent at an international school, a board member, and chair of various board committees, along with her leadership role as a school administrator, provide her with a comprehensive understanding of schools, their communities, and their operational aspects.

At ISS (International School Services), Dr. Cass is responsible for developing and delivering services that aim to enhance the capacity of school leaders and support staff to create more harmonious and effective organizations.

Dr. Cass holds a Certificate IV in Training and Assessment, a Diploma in Architecture, an MSc in International Business Management from Liverpool University, and a Ph.D. in Organizational Development and Gender Diversity at the Workplace from RMIT University.