The sea belongs to me again: Steering my disabled body through an able-bodied world

Image: The Ardnish Path on the Isle of Skye, soon to be wheelchair accessible from Lower Breakish to the sea.

In this article, Matthew Savage reflects upon his experience as a disabled, wheelchair user, of a world which was neither designed nor built by or for him; and why every physical space, including our schools, is in need of liberation.

On a coaching call recently, my dog, Luna, and I were surprised by a sudden knocking at our front door. I apologised to my coachee, grabbed my crutches and went to investigate. Our house is at the remotest edge of a small crofting township on the Isle of Skye, in north west Scotland, and so doorstep visitors are extremely rare. Usually, Luna alerts us when anyone appears even on the horizon, but her guard was clearly down, and the knocking made us both jump.

We moved to Skye in the summer of 2021, post-lockdowns and having recently returned to the UK after a decade working in the international schools sector, our two children soon to fly our family nest. Like so many itinerant educators, enriching and mind-opening though the experience had definitely been, we were determined to find roots, and this was, we hoped, to be our ‘forever home’.

It offered a remoteness that appealed strongly to my inner introvert, and with nature at its absolute grandest at our finger- and toetips, I would be able to do some of the things I loved the most, every single day, hiking, trailrunning or losing myself in Luna-exhausting walks. In fact, there was a footpath from the end of our drive, snaking across the moors to a colony of harbour seals, but one jewel on a rugged coastline I longed to explore from the rocks, a kayak, or even, if I could brave the temperature, the waters themselves.

However, the weekend before our move, I began to fall ill. A complex neurological disorder would, within just a few months, confine me to a wheelchair, completely unable to walk. Swapping two legs for four wheels, my life would change unrecognisably. Two years on, try as I might and despite the ‘disability pride’ badge occupying pride of place below my computer monitor, I am struggling to be proud of my disability, even though – with each passing day, week, month – the lines between my disability and me are disappearing completely.

Many of my everyday symptoms – the allodynia that secretly burns my skin, the angry twitches that shock my muscles, the stammer that silently benights my speech, the spasticity which tugs my shrinking legs – are invisible to others. But everyone can see that I cannot walk, and learning to navigate an able-bodied world with a disabled body has taught me so much. About our bodies and all the things we take for granted; about a world designed and built by and for those who can walk; and about the power perpetuated by that design and construction, the tyranny of physical space.

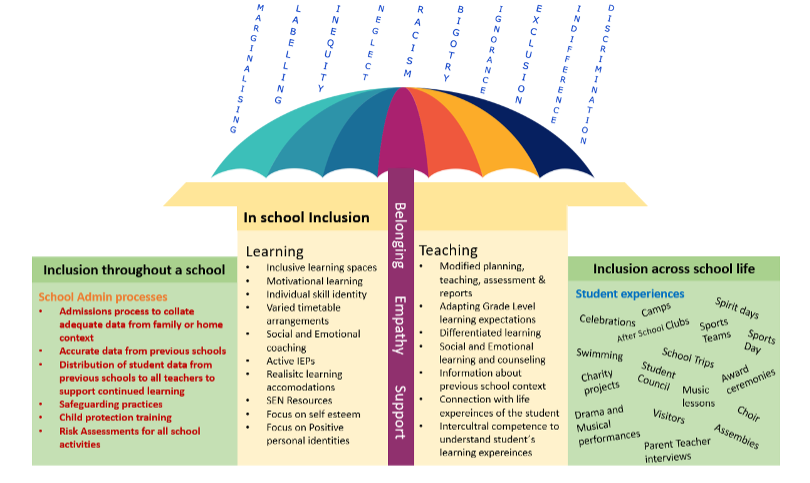

I am privileged to be engaged in a project, with tp bennett architects and in association with ECIS, in which we aim directly to challenge that power and to seek what we are calling ‘liberated school spaces’. Teams of educators, architects and students will explore how the different spaces in our schools – circulation, classroom, sustenance, personal and outdoor – can too easily exclude, marginalise and oppress the very, marginalised groups they should most seek to include. A school campus, like the world beyond its gates, is, in so many ways, an instrument of power, and that has to change.

But it is beyond the school gates that I have most experienced this tyranny myself, and I share here some small windows into my story. These snippets are about planes, trains and automobiles; about bathrooms, doors, and bathroom doors; and about curb cuts, actual and metaphorical. Because all of these have, in their own way, kept me on the margins of society; because I know that my ‘protected’ characteristic is unprotected, tyrannised even; and because each of these spaces could, and should, be liberated.

Beyond the safe and known confines of our Highlands bungalow, I navigate any internal or external space in my electric wheelchair. The ‘door’ is a convenient metaphor for the portal to any community of power (we talk about getting our ‘foot in the door’, for example); but that portal, for me, is literal. If I want to enter or exit any building, or room therein, I am typically faced with a heavy, handled, hinged, outward-opening door, despite the fact that the only door that is easy and safe to open in a wheelchair is a sliding door, manual or, better still, mechanised.

This challenge is everywhere, in many an ‘accessible’ hotel bedroom, and especially so when I want to enter an ‘accessible’ bathroom. Almost every time I have wanted to use a public bathroom, I have had to ask a stranger if they would open it for me. As someone who does not believe students should have to ask for permission to use the bathroom, I certainly do not think I should have to do so myself. To add insult to injury, many an accessible bathroom does not provide sufficient turning space either; and flying out of one airport recently, I was told there was no accessible bathroom available at all.

As a consequence, I commonly try to minimise my fluid intake when out of my house, so that I do not have to suffer the indignity of a bathroom whose ‘accessibility’ is but a mirage, a performative badge that may tick boxes but does not liberate the disabled user. This is not to mention the bizarre requirement in many a public space that a wheelchair user report to a cashier in a nearby shop to collect, and return, the special bathroom key. I recognise this is to ensure able-bodied users do not occupy this targeted space – but, again, the design, much as it may seek to liberate, does anything but.

Whilst I love the success with which Zoom masks my disability, I love my face-to-face work. Norah Bateson calls this aphanipoiesis, the communing and commingling of multiple stories in a submerged, liminal space from which could eventually emerge a seedling of hope. And for me, professionally, nothing compares to this; how fortunate am I that the pandemic lifted its pall such that I can safely travel around the world again. And yet each flight, or succession thereof, treads on my agency and dignity, and my comfort and safety, at every juncture.

The system through which one requests special assistance when booking a flight varies between airlines in all but one thing: its complexity. Even airlines which build it into the booking process rarely pass this information on to the check-in staff, leaving me having to explain my medical condition and requirements again, all in earshot of an increasing, and increasingly irritated queue. And most airlines require persistent and repeated phonecalls and emails to secure a promise only that they will endeavour to provide said assistance.

I used to rely on the airport wheelchairs, but the understaffing of the privatised assistance teams, combined with the fact that most airport wheelchairs are not self-propelling, left me, too often, stranded in a corner, facing a wall, without access to food, water or a bathroom for several hours. Therefore, I invested in a foldable, electric wheelchair, which is now, to all intents and purposes, my legs. Just as I manage, despite numerous objections, to take it to the plane door, I am always promised that it will be returned to the door on landing; but, on landing, I am commonly told that it has been “lost”, panic setting in until it is discovered again, somewhere in the baggage hall.

Going through security is, at best, undignified and, at worst, invasive; on only one occasion have I been permitted to take my wheelchair onboard, and so my agency is taken away with it; boarding is a spectacle, whether or not I manage to avoid being forcibly strapped into the onboard wheelchair; the safety instructions, written or spoken, never mention someone like me; my crutches are routinely confiscated, and retrieving them, should I need the (inaccessible) bathroom, is laboursome.

And, on landing, it is not uncommon for me to remain on board for up to an hour after everyone else has disembarked, the crew for the following flight patiently caring for me until assistance has arrived. Every flight I take takes away a little part of me, and I am lesser forever thereafter. And yet, with intentionality, consultation and compassion, air travel is a space that could easily be liberated. The likes of Sophie Morgan fight this fight on my behalf; I used to give feedback myself, but nothing ever changed, and it is hard then not to give up on feedback altogether.

I love curb cuts. Designed in California by Ed Roberts and others in the 1950s and 1960s, they took one of the discriminating spikes of hostile architecture, and literally excised it to create a ramp that directly benefits people like me, but from which everyone else also benefits. Such a powerful idea is this that I use its metaphorical equivalent as one of the instruments of equity and justice through which every aspect of the school experience can be adapted for universal belonging.

However, whenever I navigate the pavements of a city, I have learned not to depend upon the existence of the actual curb cuts which would enable me to move, unencumbered, through those built environments. The only city where I have not faced this difficulty was Amsterdam, but this is because of the prevalence, far further up the food chain, of the bicycle; the wheelchair was an afterthought. I often talk to schools about the tussle, in any practice, between coincidence and consistency, and this is, fundamentally, an equity issue. The same is true for the humble curb cut.

In London recently, I selected a restaurant based on its social media and website having declared it fully accessible, only to arrive and find there was a step to enter the premises. This is not just frustrating; it is humiliating, distressing, and infuriating. The step may as well be a brick wall. Then there is the construction work which has temporarily diverted pedestrians on to the road, but without a ramp to cut that curb. And on a recent train journey, a step-free station was closed, which meant I had to ask several strangers to lift me, on my wheelchair, from the train at the next station.

Which brings me to the ramps, installed or designed with the best intentions, deliberate acts of inclusion, whose gradient is simply too steep to carry my wheelchair safely upwards. On at least three occasions this year, it is only the sharpest reflexes of a group of adults coincidentally nearby that prevented my wheelchair tipping backwards and sending me tumbling to likely serious injury below. Or the promised ramps which, for whatever reason, did not materialise, leaving me depending, again, on others, this time to lift me up the steps to the upper level.

I share none of these stories, any more than I would the myriad other stories I kept back, to elicit pity. No disabled person I know wants that. I only aim to offer a window into the tyranny, intentional or otherwise, of the able-bodied over those whose body is disabled, but one example of the power exerted by physical spaces over those for whom said power is but a pipe dream.

Too often, the burden of fighting for accessibility, equity and justice falls to those on the margins. Some schools I visit thank me for shedding a light on the inaccessibility of their campus; it is not uncommon for a school to ask a queer educator (or student) to educate the school on the harm of a cis-/hetero-normative curriculum, culture and climate; and many a school will finally seek to adapt to the needs of the minoritized only when an educator or student happens to inhabit that particular minority. And yet, as my own story epitomises, disability is a characteristic that could suddenly strike any one of us, temporarily or permanently, at any point of our life.

Consequently, I have had no choice but to adapt myself and my life to a world which has not, nor will it, adapt to me. The crutches offered to me, by default, collapsing bruisingly beneath my faceward-falling body too many times, I commissioned bespoke crutches which not only could bear my full weight but also came with attachments for mud, sand and even snow. And I invested in a disability-adapted, fully recumbent, motorised trike, on which I can now explore the lanes and byways of rural Skye, without depending upon anybody else.

Meanwhile, let us return to our unexpected visitor, knocking to the surprise of Luna and me in the midst of my coaching call. He was part of a team, funded by the charity, Paths for All, who were rendering fully wheelchair-accessible the entire footpath from the end of our drive to the rocky shore in the distance. And he wanted to inspect my trike, to make sure that the sharpest bend in the new path could accommodate its particular turning cycle.

I may cry easily these days, but I was moved to tears by this gesture. The view from my front room, until now teasing me with a landscape that I could only watch and imagine, was soon to be liberated. Both natural and built environment were bending to my needs, and the power was shifting. Very soon, I would be able to cycle to the sea, for the first time since we moved here. The seals may not have missed me, but I have certainly missed them; and, in this space, for the first time, I would finally feel free. I have yet to manage kayaking, and I cannot swim any more, but still, in a small but significant way, the sea belongs to me again.

The “Liberated School Spaces” conference, a collaboration between tp bennett, ECIS and The Mona Lisa Effect®️, will take place in London on 10 November 2023. Learn more and register here

A proud member of ECIS’ DEIJ team, Matthew Savage is an experienced, international school principal, governor, speaker, coach and consultant, helping leaders, educators and students worldwide, through The Mona Lisa Effect®, help ensure that every child, without condition or exception, can “be seen, be heard, be known and belong”. He lives on the Isle of Skye, with his wonderful wife and atypical dog.