LIMIT – A Model for Understanding Healthy Teacher-Student Relationships

Dallin Bywater

School Counselor

Academic research underlines the importance of positive teacher-student relationships for creating an effective education environment (Hamre & Pianta, 2001; Baker, 2006). While this truth is well known, the intricacies of how to develop and maintain a safe and positive relationship with students is less understood. In fact, teacher behaviors that are intended to engender a supportive relationship may actually be risky and unhealthy in practice.

Experts have identified four risk factors for unhealthy teacher-student relationships (Wolowitz, 2006):

1. A relationship power imbalance

2. Poor boundary setting

3. Role confusion

4. Isolation

All four of these risk factors are common in international schools. By understanding and providing training to educators to mitigate these risk factors, both teachers’ and students’ wellbeing will benefit.

The first risk, a power imbalance, is inherent in a teacher-student relationship. All teacher-student relationships include a difference in power because the teacher is an adult in a position of power, and the students are children or adolescents.

The second risk, poor boundary setting, can easily occur due to the transitional nature of international living. Professional boundaries are limits in a relationship that protect the space between the professionals power and the student’s vulnerability (NCSBN, 2018). There are various personal factors that can increase the likelihood of poor boundary setting. For example, when teachers or students move to a new school, naturally personal boundaries are loosened in order to get to know people, and make new friends. Additionally, teachers and students often do not have extended family nearby, creating an emotional void that can lead them to look for emotional support from other relationships.

Third, role confusion, occurs when individuals are in an environment where personal and professional life frequently overlaps. For an educator in a small international community, the lines between parent, educator, coach, family friend, and/or other identities can be blurred. A teacher’s social circle and work circle have considerable overlap. Blurred identities are a hallmark of role confusion.

Lastly, isolation is a risk factor because there are opportunities for one on one interaction in residence halls, classrooms, health or counseling centers, and other locations on campus.

Two further complications to teacher-student interactions include the complex cultural influences on social behavior at international schools, and the various training backgrounds of educators in the school. Each culture has unspoken rules about appropriate social behavior. An international community may contain a spectrum of high and low contact cultures, and high and low context cultures which impact social behavior (Bywater, 2021). While this diversity is overall an unquestionable strength, it is also important to recognize that amalgamated cultural expectations about acceptable student-teacher interactions can be nebulous, and the training worldwide about teacher-student boundaries varies immensely. Some teacher training programs include strong expectations and education about healthy boundaries, while in other programs it is nonexistent. Culturally, the norm for interactions between teachers and students in some countries might be considered nurturing and positive, while teachers of a different cultural background may consider the interactions highly unethical. A visible example would be physical boundaries – some cultures encourage touch between students and teachers, while others may forbid it due to concerns of allegations, and/or respect for student body autonomy.

Learning about and applying boundary-setting skills can reduce the risk factors described above. Having awareness of the power imbalance between students and teachers, knowing how to set firm boundaries, and avoiding overlapping personal identities are all part of developing healthy relationships. It is important that each school community clearly communicates to staff, students, and the community what is acceptable in regards to staff-student interactions, and what relationship-building behavior is appropriate. Clarity in guidelines and policy supports the wellbeing of both staff and students, and prevents unnecessary confusion and potentially damaging allegations.

The LIMIT Model

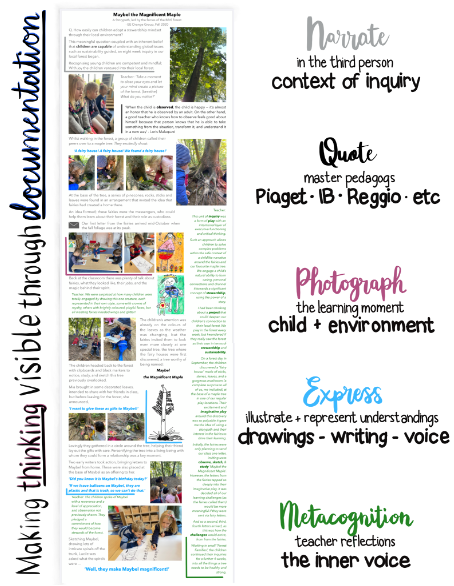

The following model, aptly named LIMIT, has been developed to guide the discussion and training of education staff about healthy teacher-student relationships.

While the model described below may appear to be directed at teachers, the information applies to all school staff and can be used accordingly. The recommendations provided are generally applicable, however, what is appropriate for your school community may be different depending on the culture of the school and country laws and norms where you reside.

L– Location

I – Internet

M – CoMmunication

I – Identities/Roles

T – Time and Touch

Location

Location refers to the places that an educator’s interactions with students occur. Interactions with students should be viewable by others. A few other recommendations include:

- Do not allow students or their parents parents to be in your home.

- Do not go into a student’s home.

- Avoid weekend social locations (e.g. clubs and bars) where students might be present.

- Avoid locations where you may be alone with a student.

Internet

Internet refers to communication done over devices – social media, texting, and other mobile phone services to name a few. Some professionals estimate that around 90 percent of inappropriate teacher-student relationships start through texting or social media (Millweard, 2017).

- Interactions with students online should be done on school platforms

- Online interactions should reflect the same language and behavior that you would use in person

- Students should not be added by teachers as Facebook friends, or on any other social media platform.

- Set professional limits on when, how, and on what platform you will communicate with parents and students.

- Photos of students should not be posted on your social media accounts

- School guidelines should limit student photo taking and video recording for specific learning purposes, and delineate proper storage and destruction of these files.

CoMmunication

Communication includes the content and connotations of words used with students.

- Avoid making any comments about a student’s body.

- Be aware of what personal information you disclose. For example, students do not need to know where you live or what is happening in your romantic relationships. Any personal disclosures should be purposeful and meet the needs of students.

- Students should be asked to call you by a culturally appropriate, respectful title. In many cultures, addressing you solely by your first name, nickname, or name that your friends call you can imply that your relationship is something more than teacher-student.

- Maintain confidentiality of all student and staff records (including health, disciplinary, academic, etc.).

Identities/Roles

Teachers must maintain their identity as a teacher and avoid mixing this identity with other personal identities at school. A common way to conceptualize identities is wearing hats. Each role identity is a hat. Professional, balanced decisions and healthy relationships are best accomplished when a person avoids wearing multiple hats at the same time. Misunderstandings occur when multiple hats are worn together. This principle can be particularly challenging for teachers who have children in the school, because it is difficult to separate the roles of parent and teacher.

- Always remember that you are the teacher, not a student’s parent or friend. Having a positive, supportive relationship is not the same as being friends.

- Be aware of your overlapping role identities, and how they affect your professional relationships.

- Wear one “hat” at a time whenever possible.

- When interacting with students and other staff, ask yourself what role you are acting in. As a teacher? A parent? A friend? Is it clear to the individual which role you are in?

- If you feel a role conflict, excuse yourself from decision-making capacities related to the situation. For example, if you are the principal and your child has entered disciplinary procedures, you should excuse yourself from the proceedings.

Time and Touch

Time refers to the amount of time a teacher spends with a student. Recommendations include:

- Set limits on when students and parents should communicate with you (e.g. before 5pm).

- Only meet with a student during work hours for academic-related purposes.

- Avoid allowing a student to dominate your break and lunch hours.

Touch refers to any physical contact between a teacher and student.

- Any touching should be viewable by others.

- Consider the cultural expectations of touch, including how it could be perceived and received.

- Context is important – a goodbye hug at the end of the school year is different from an unsolicited hug.

- Examples of appropriate touch may be a handshake, high-five, or hand on the high back or shoulder. This can be culture-dependent.

- Whenever possible, ask permission before touching (ex. “Can I put your hands on the proper place of the tennis racquet?”)

Practically every day teachers encounter situations where it is important to set boundaries with students. In many cultures, adolescence is the time of testing and pushing boundaries, and it is the adult’s responsibility to set an appropriate boundary, and keep it.

The LIMIT model provides a simple way to begin school dialogue about professional relationships, and helps staff conceptualize appropriate behaviors. Many recommendations appear to be common sense, but administrators cannot assume that teachers are clear about appropriate teacher-student behaviors. The high turnover in international schools, diversity of cultural expectations, and variability in teacher training programs make boundary training an essential element of any international school professional development plan.

What Positive Teacher-Student Relationships Look Like

In addition to mitigating the risks of unhealthy teacher-student relationships, other strategies can contribute to creating healthy relationships. Researchers generally agree that the following are qualities of healthy teacher-student relationships:

- supportive, but not overly dependent

- high and realistic expectations (Downey, 2008)

- honest and trusting

- strives to be conflict-free

- teacher uses learner-centered practices

- teacher encourages positive relationships among students

- mutual respect, caring, and warmth (Birch & Ladd, 1997)

Some other ideas for developing positive teacher-student relationships can be found here: https://www.apa.org/education-career/k12/relationships

Considerations for Administrators

When teachers have opportunities to understand and be empowered to set appropriate boundaries, it is an opportunity for self care, further benefitting the school environment. Teachers need to know from administrators that they are expected to set healthy boundaries, and that their leadership team will support them in this process. Imagine the relief that some teachers may feel if an administrator tells them they are not expected to read or answer emails past 5:00pm.

In addition to providing adequate training and support, administrators are responsible to monitor and give feedback to staff regarding boundaries. Feedback is necessary when boundaries are loose. Unhealthy and inappropriate relationships rarely occur suddenly – rather, boundaries are slowly relaxed over time until there is potential for the occurrence of completely inappropriate behavior. The following can be warning signs of poor educator boundaries:

- secret conduct

- oversharing personal information with students

- behavior showing favoritism (Feeney, Freeman, & Moravcik, 2020)

- minimal separation between work and personal life

- acting in a peer, friend, or parental role to students

- dependency meeting a teacher’s need

- repeated boundary crossing, even if it appears insignificant or harmless

International school administrators, counselors, and other support staff can use the LIMIT model to provide common language for learning about, discussing, and establishing healthy boundaries in teacher-student relationships. This dialogue can extend past country lines and diverse education models.

At one international school, an hour of professional development time each year was dedicated to healthy boundary training. The resulting discussions clarified the school’s expectations, shed light on cultural differences, and raised important questions that teachers had regarding their interactions with students. The training also opened the door for yearlong dialogue with teachers and staff about boundaries. All four risk factors of unhealthy relationships were brought to staff awareness with a short amount of formal dedicated time, and the guiding principles of healthy teacher-student relationships were reaffirmed in future informal conversations.

Prevention is paramount. Organizations where boundaries are fully adhered to are likely the safest environments for children (Eastman & Rigg, 2017). Targeted professional development and correcting initial loose boundaries may minimize the probability of teacher misconduct with students, where the resulting harm and tragedy has no bounds.

REFERENCES

Baker, J. A. (2006). Contributions of teacher–child relationships to positive school adjustment during elementary school. Journal of School Psychology, 44, 211−229.

Birch, S. H., & Ladd, G. W. (1997). The teacher–child relationship and children’s early school adjustment. Journal of School Psychology, 35, 61−79.

Bywater, D. (2021). Touch in International Primary Schools: A Practical Approach with a Cultural Lens. ECIS Insightful.

Downey, J.A. (2008). Recommendations for fostering educational resilience in the classroom. Preventing School Failure, 53, 56-63.

Eastman, A., & Rigg, K. (2017). Safeguarding Children: dealing with low-level concerns about adults. May 2017, www.farrer.co.uk/news-and-insights/safeguarding-children-dealing-with-low-level-concerns-about-adults/

Feeney, S., Freeman, N., & Moravcik, E. (2020). Boundaries in Early Childhood Education. Young Children, 75, No. 5. https://www.naeyc.org/resources/pubs/yc/dec2020/professional-boundaries

Hamre, B., & Pianta, R. (2001). Early teacher–child relationships and the trajectory of children’s school outcomes through eighth grade. Child Development, 72, 625–638.

Millweard, Christy. “Fed up: Leaders Battling ‘Alarming Rate’ of Inappropriate Teacher-Student Relationships.” Kvue.com, 28 Apr. 2017, https://www.kvue.com/article/news/local/fed-up-leaders-battling-alarming-rate-of-inappropriate-teacher-student-relationships/269-434295513.

Wolowitz, David, Bluestein J., & Broe K. (2006). Boundary Training in Schools, United Educators Roundtable Reference Materials, December 2006.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Dallin Bywater is an international school counselor on hiatus. He has presented for parent and teacher workshops, and has published articles on a range of topics related to student mental health.

bywatercounseling@gmail.com