A Partnership Approach: Empowering Collective Efficacy through Data, Collaboration, and Alignment

Montessa Muñoz, Educator

Chad Dumas, Consultant and Author

It is no secret that the belief that one’s actions impact others is tightly correlated with actual improved student learning. Some might call it self-fulfilling prophecy, others efficacy. Going back to the Pygmalian in the classroom research (Rosenthal and Jacobsen, 1968) we know that teacher expectations drive student performance. And more recent research from Hattie (2018) places this concept among the highest predictors of student achievement. We as educators and schools can, do, and will improve outcomes for kids to the extent that we believe that we actually can.

Knowing this is true, however, does not make it magically happen in schools. It is only the first step. Developing a strong sense of collective efficacy, built upon individual educator efficacy, happens through deliberate actions focused on instructional practices (as opposed to mere managerial issues). Our experience, as a building principal supported by a district administrator, is that both levels of the system support and enhance each other. As such, we will highlight three major areas of our partnership: the collection and use of data, collaborating on instructional improvement, and aligning a culture committed to student success.

Background

Prior to an in-depth look at these three areas, let us provide some background. The setting from which most of these experiences derive was a high-poverty, high-diversity, lower-performing school and district. When Montessa arrived as principal (one year following Chad’s arrival at the district level), the building had grade-levels with the percent of students proficient on various benchmarks near single digits. Despite having more than 90% of students from poverty with a high proportion of English Language Learners (ELs), through the application of the ideas presented below, the school became a national model and achieved more than 90% of students reaching benchmark on multiple assessments.

We know that Professional Learning Communities (PLCs) are an effective route to building collective efficacy (Voelkel and Chrispeels, 2017), and our district’s first priority was in doing this work. As such, from a district perspective, we honed in on the advice of DuFour, Dufour, Eaker, and Many (2010). For a more detailed discussion, please see Dumas and Kautz (2014); suffice it to say that the district emphasized three areas for leading PLC implementation: Limit initiatives (i.e. focus the work), build capacity, and create systems for mutual accountability. For the purposes of this article, we will focus on building-level actions taken to build individual and collective efficacy.

The collection and use of data

Building individual and collective efficacy, in our experience, is grounded in the collection and usage of data. Data was collected by students, teachers, principal, and central office staff. It was posted in classrooms, along hallways, around the cafeteria, in the staff lounge, and on the desk of the principal. In central office, the main conference room displayed data from administrator learning meetings, and a spider-like radar chat was prominently displayed in the office of the director of learning. Data could not be missed.

The weekly newsletter to staff from the principal listed goals and progress. Instructionally, 80% of students were to be on-task in any given classroom, and the principal collected and reported this weekly from classroom walkthroughs. For reading and mathematics, data was charted weekly, and scores on the school-wide common writing rubric was charted monthly.

In order to display the data, it had to be collected. Progress monitoring was previously done by non-classroom teachers. This changed (with some push-back, but surprisingly little). Classroom teachers are the rightful owners of progress monitoring and the data provided by this work. District common assessments and benchmarks, DIBELS, easyCBM, and common team-based formative assessments (known as LtoJ in our case) formed this foundation.

Having the data collected and displayed is only the beginning, though. The more important work is in talking about it. All. The. Time.

Data was a focus in evaluations, PLC meetings, at the start of each staff meeting, and in school-wide daily announcements about student and classroom “All-Time Bests” (ATBs). Student artifacts were shared by staff in team and school meetings, building confidence of staff as they talked about what they saw from students. And, believe it or not, students themselves, all the way down to kindergarten, were involved in graphing and tracking their own and the classroom’s progress.

Images 1 and 2: Students chart their own progress—including Kindergarten

Office referral data was reviewed once per month by the Positive Behavior and Intervention Support (PBiS) team. Attendance data was reviewed weekly by a team that included the principal, counselor, nurse, and social worker. Math and reading benchmark data were formally reviewed three times per year.

A partnership with the University of Nebraska helped build capacity to collect meaningful student performance data, set decision rules, configure aim lines, and adjust practice accordingly. Little by little, over time, our mindset changed around data. It changed from expecting someone else to hand us some standardized test score to us doing the collecting, analyzing, and using our own, far more meaningful results of students’ learning. Needless to say, seeing the impact of our work on students built efficacy both individually and collectively.

Collaborating on instructional improvement

Just collecting and using data, by itself, however, does little to increase efficacy. This work must be accomplished with learning to improve our practice so that the results will improve. Enter a laser-like focus on collaborating for instructional improvement.

In combination with district-wide efforts, the school had a total of four areas of focus: 1) Engagement strategies, 2) Explicit phonics and vocabulary instruction, 3) Four Block Writing instruction, and 4) Social-Emotional Learning/Proactive behavior strategies.

Regarding engagement strategies, we sent four staff members to a national Kagan training to then come back and help other teachers develop these skills. Not only did this experience build the capacity of these four staff members to be better at engaging their students, but they then taught other teachers how to implement these strategies. Efficacy became integrated into their identities.

The same research project from the University of Nebraska mentioned earlier helped focus on explicit instructional practices. The intense focus on these strategies to teach phonics and vocabulary instruction were then a focus of professional learning and data collection. For example, frequency of choral and physical responses, the use of white boards for formative assessment, and tracking the explicit use of research-based vocabulary instruction strategies to ensure students know and can apply key words.

Figure 1: A walkthrough observation form used to collect and use instructional data

The district had embarked on a four-block writing strategy years before, and school leadership decided to reinforce this work. Staff learning, PLC conversations, and data collection were key tools in ensuring the quality and fidelity of implementation of these practices. Further, the school used vertical teams (K-2 and 3-5) that included EL, Title, and Special Education to ensure consistency of language and structure for writing instruction. And a school-wide rubric was developed and used on common writing prompts to track progress and inform changes to practice. Finally, writing exemplars were identified and reviewed regularly to create a standard of quality writing in the school.

Finally, understanding and proactively addressing SEL and behavioral issues was a focus of the school. We know that students must feel safe, and the adults in the building are responsible for doing this. So the school implemented “families” where each adult led a group of six students (one from each grade level) who met throughout the course of the year to build community and relationships with each other. The school also worked diligently to faithfully implement PBIS to ensure that our core processes and interventions were helping all students self-regulate. Part of this involved holding Friday assemblies to celebrate team and individual accomplishments of students and staff. And finally, the counselor taught “Second Step” materials while teacher’s facilitated classroom meetings.

Aligning a culture committed to student success

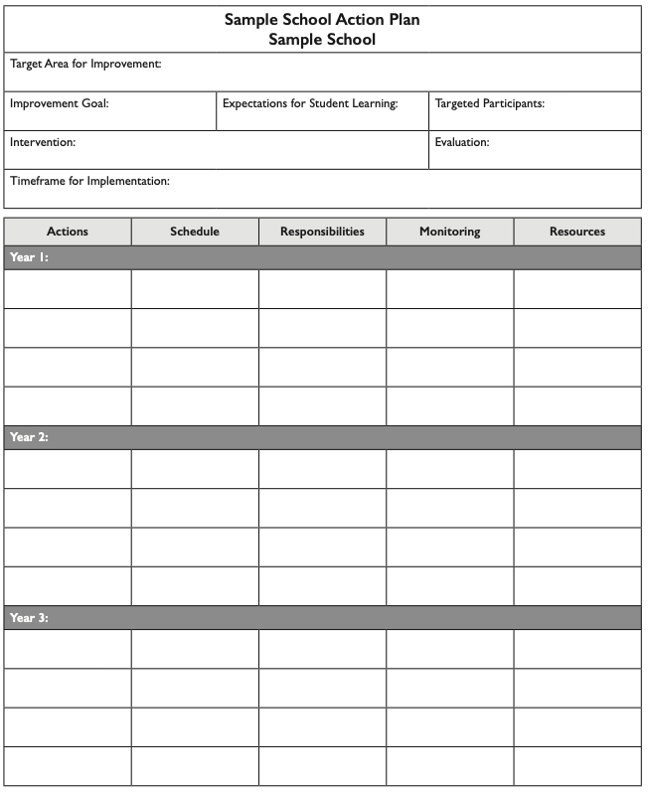

Developing individual and collective efficacy, grounded in data usage and an instructional focus, manifests itself in a culture that is committed to student success. In our work, this culture was advanced through the alignment of several structures: High expectations, Practices, and Teaming.

Using data and focusing on instruction will do little good without high expectations–for each other and for each student and family. This begins with learning each student’s name, and ensuring that we are not “dumbing down” expectations based on race, socio-economic status, gender, or other characteristic. Further, it involved celebrating successes for students, as well as staff–both individually and in teams. And it involves ensuring that instructional practices are in accordance with having high expectations (Marzano, 2007).

Finally, high expectations shows up in how we partner with families. We found parents ready and willing to help with translating, interpreting, and providing food for myriad events. We encouraged their involvement in other ways, too, like in the structured Dads of Great Students (D.O.G.S.) program, and in providing lists of how and when parents could volunteer for the school.

Second, this culture required the alignment of multiple practices. All work aligned towards the identified school improvement goals. This included ensuring that monthly professional learning time focused on the priorities, and that teachers were the ones leading the professional learning.

Previously-identified interventionists transitioned to instructional coaches. They were trained in Jim Knight (2007) processes, and attended monthly support meetings and trainings with other coaches across the district. These same coaches led instructional rounds with staff throughout the building in an effort to de-privatize practice. And the coaches met with the principal once per week to plan specific professional learning and supports.

Finally, the high expectations and alignment were reflected in how the school worked as a team. Grade-level teams met at least two times per month. Vertical teams (K – 2 and 3 – 5) met once per month to blind-score student writing samples based on the school-wide rubric. And grade-levels from across the district met the remaining one time per month for establishing common district-wide expectations.

Figure 2: A sample action planning tool to assist with aligning all priorities

Closing

Efficacy is built on collaboration. While compliance may get short-term results, long-term gains and sustainability will only happen through working together. This means that all levels of the system are collaborative, for we can’t expect principals to build collaborative environments when the district is top-down and compliance-oriented.

The work of building efficacy is hard. Mindsets don’t change overnight. Creating an environment of caring for kids that includes high academic standards is completely doable. The work of collecting and utilizing data, collaborating on instructional improvement, and aligning a culture focused on student success can happen in any school and district. And the partnership approach between the district and school are fundamental. The question in our minds isn’t, “Can we do what it takes to meet the needs of every child?” Rather, it’s “When and how will we start?”

Bibliography:

DuFour, R., DuFour, R., Eaker, R., & Many, T. (2010). Learning by doing: A handbook for professional learning communities (Second edition). Bloomington, IN: Solution Tree.

Dumas, C., & Kautz, C. (2014). Wisdom from the factory floor: For best results, limit initiatives, build capacity, and monitor progress. JSD, 35(5), 26-34.

Hattie, J. (2018). Collective teacher efficacy (CTE) according to John Hattie. https://visible-learning.org/2018/03/collective-teacher-efficacy-hattie/

Knight, J. (2017). Instructional coaching: A partnership approach to improving instruction.

Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin.

Marzano, R. J. (2007). The art and science of teaching: A comprehensive framework for effective instruction. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Rosenthal, R, and L. Jacobsen. Pygmalion in the classroom: teacher expectation and pupils’ intellectual development. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1968.

Robert H. Voelkel Jr. & Janet H. Chrispeels (2017) Understanding the link between professional learning communities and teacher collective efficacy, School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 28:4, 505-526, DOI: 10.1080/09243453.2017.1299015

What do you think about the points raised in this article? We would be delighted to read your thoughts below.