Differentiation and Inclusion

Differentiation and Inclusion

Martha Ross

Different or Included?

What motivates us to adapt or differentiate learning to create equity in our classrooms?

The inclusive education context that we experience every day is likely to differ across the diverse contexts of international schools. As national systems and accrediting agencies seek policy and practice that promotes diversity, equity, and justice in education, inclusion is the term that we use to describe and foster this practice.

Daniel Sobel, in his paper entitled, ´Inclusion is a verb: Belonging and schools´, highlights the characteristics of an inclusive school where students are equally important in the community, students are heard and respected, all school facilities are accessible to all students, access to quality education is available for all students, etc. (Sobel, 2022). It is therefore important to recognise who is in our student population and to ask, how we can strive for equitable school experiences and make this a priority.

Then comes the operational question; what is it that motivates everyone in an international school community to adapt their practice to include a wide range of divergent students?

Currently, the answer to this question is a requirement for teachers to differentiate learning. Essentially we ask teachers to design and create learning for the majority of students and then consider different learning experiences for individual students. The pressure of curriculum coverage however can drive us to consider deficits in learning development before we make time to look for individual strengths. If we could reframe the process of differentiation and balance student strengths and learning needs, we could create more inclusive practices.

What motivates us to adapt or differentiate learning to create equity in our classrooms, is never more important than now. Sufficient knowledge about our learners is fundamental to our understanding of effective inclusion. Ellis, Kirby, and Osborne, (2023), recently published an insightful book, ´Neurodiversity and Education´ which clearly outlines the opportunity to address cognitive differences. This work gives us the opportunity to understand how to support and promote our neurodivergent students, knowing that they all bring with them unique skills and competencies. Using the model of Universal Design for Learning, the book illustrates how to create inclusive and therefore more equitable learning contexts.

‘Many of the challenges that our neurodivergent students face are not distinctly different to the challenges that we all face, but tend to be more exaggerated.‘ (2023, Ellis et al).

Researchers such as Daniel Sobel open our minds to the reality of school life as a highly sensory experience. Educators themselves who share the experience as neurodivergent learners can be powerful motivators to colleagues and students for successful learning.

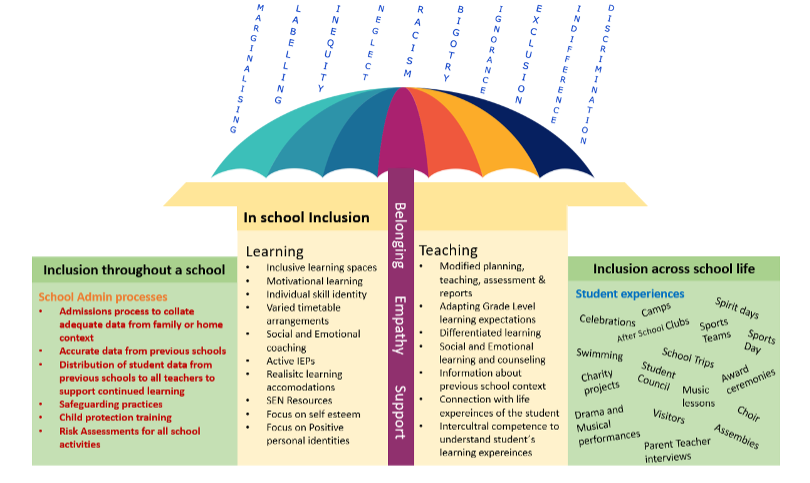

Inclusion, or the process of successfully including all students, provides an opportunity to consider education and schools from a new perspective. We can learn from our communities, from the individuals that we strive to include, and then reframe our perspective accordingly. This inclusion model by Thompson, (2022) provides a visual of the importance of knowing whom we are supporting in our school communities.

In addressing our motivation toward inclusion and equity in the classroom;

- Can we reframe support for neurodivergent learners by identifying skills and learning support needs?

- Can we address our perception of differentiated learning and work towards collaboration and not separation?

- Can we as teachers, SEN and Inclusion coordinators draw students into the group, to share, collaborate or contribute towards learning, according to interest and ability?

Instead of focusing on learning differences, we are considering experiences so that all individuals contribute to a community of learners. The adapted inclusion model shows how we can come together and protect everyone by fostering a culture of belonging, empathy and support.

The answer to the question addressing teacher motivation is perhaps addressed with training for teachers in Universal design for learning. Ellis et al, describe this process as, The Why, (engagement) – how can we motivate students and sustain their interest? The What (representation) – providing information in different formats and The How (action and expression) – how will the student demonstrate learning and understanding to others and for themselves, (2023, Ellis et al).´ These are all vital skills for inclusion to occur in international schools.

At the recent ECIS conference, Leading Inclusion by Example, at the American International School in Athens, insightful keynote speakers led a conversation centered on the school experience of all students. This conversation became focused more specifically on our neurodivergent students and their learning contexts. This experience led the conference participants to carefully consider strategies that could help teachers connect with all learners.

Dr. Judy Willis shared strategies to reduce boredom and frustration by considering neuroscience research and ways to open the attention filter and tap into the motivation of the students. We learned to share the task of addressing attention and focus by talking to the students directly. There is an opportunity to establish a shared understanding of what distractions there are in our learning environments and how to eliminate them by asking those who experience it.

Daniel Sobel, called the whole group of conference participants, ´Inclusionists´. He modeled how we can actively try to understand student behaviours by learning more about students´ life experiences and how their neurodivergence impacts the learning environment. This focus led the conference participants to understand the importance of the learning environment from the perspective of the student.

Nicole Demos created a moment in time by sharing her life experience as a disabled member of a school community and as an adult living internationally in different societies. We learned who were the inclusionists in her life, those who championed her success and achievements. Nicole shared where she wishes she had sought greater access to the whole school experience. This led her to bravely share her story and acceptance of her disabled identity.

These messages can and should reach far into our classrooms to ensure all our students have equitable access to all aspects of school life. This is illustrated in the final model where the Inclusion umbrella protects the school for all students enjoying all school experiences. In reframing how we approach equitable learning environments, a call to school leaders will be required to redistribute time and create space to consider Inclusion and promote Belonging, Empathy, and Support for the whole community.

(Model adapted from Thompson, 2022)

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Dr Martha Ross is currently an Inclusion Coordinator at International School Carinthia, Austria. She recently decided to refocus her career in the direction of Inclusion and Student Support after seven years in Senior Leadership. Martha is motivated towards the positive identification of all students in an International School Setting. During her post graduate studies, Martha focused her research on Inclusion and Intercultural Competencies.

REFERENCES

Demos, N. (2023) Keynote presentation. ECIS Inclusion Conference, American International School, Athens. March 2023.

Ellis, P, Kirby, A, Osborne, A. (2023) Neurodiversity and Education. Sage Publications. Pages 76, 87.

Institute of Neurodiversity – https://ioneurodiversity.org/about-us. Sourced March 2023.

Sobel, D. (2022) ´Inclusion is a verb: Belonging and schools´ sourced October 2022. https://www.sec-ed.co.uk/best-practice/inclusion-is-a-verb-belonging-and-schools-send-vulnerable-students-mental-health-wellbeing-safeguarding-children-young-people/

Sobel, D. (2023) Keynote presentation. ECIS Inclusion Conference, American International School, Athens. March 2023.

Thompson, L. (2022) Inclusion Umbrella. Who does InclUSion protect? Model.

Willis, J. (2023) Keynote presentation. ECIS Inclusion Conference, American International School, Athens. March 2023.

Freepik image sourced April 2023. https://www.freepik.com