Integrating core values to improve team culture and character

Luther Rauk

Middle School PE Teacher and coach, The American International School of Muscat

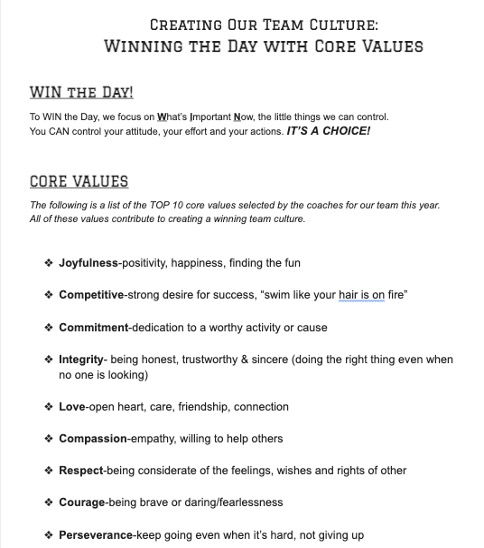

After attending the Way of Champions Coaching Conference in Denver, CO in the summer of 2019, The swim coach, Cori Lee, at The American International School of Muscat, Oman decided to implement a strategy she learned about Core Values with her swim team.

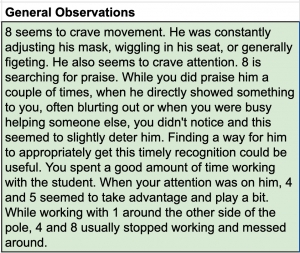

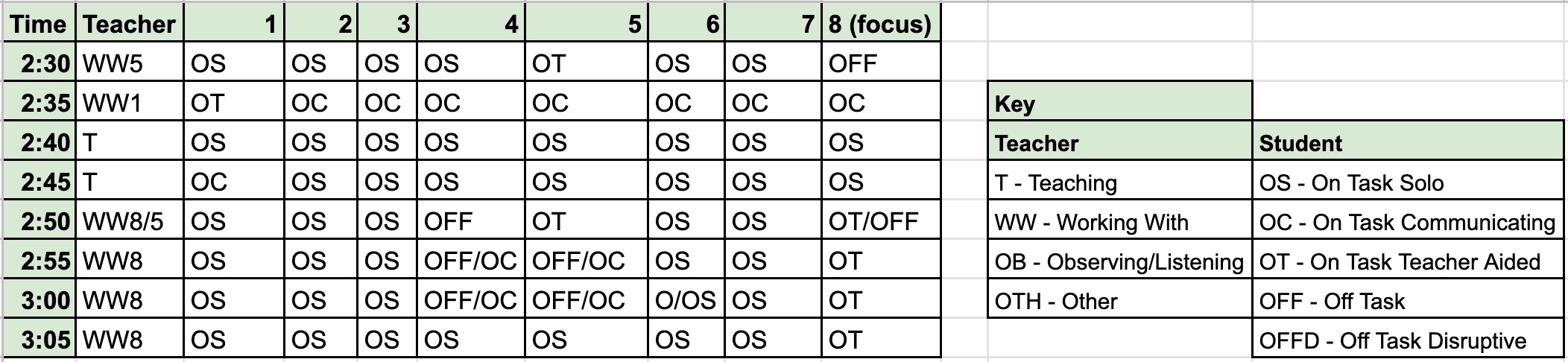

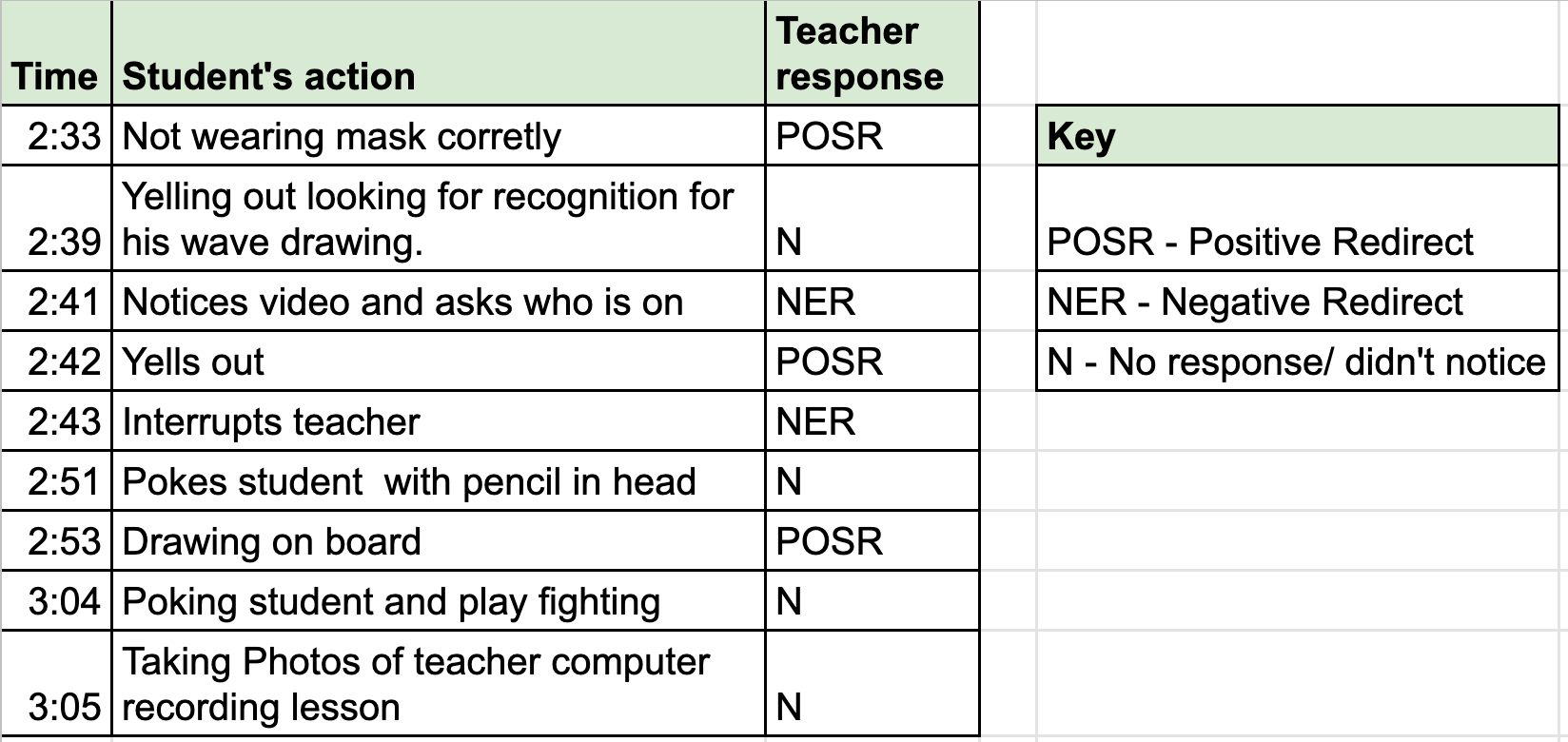

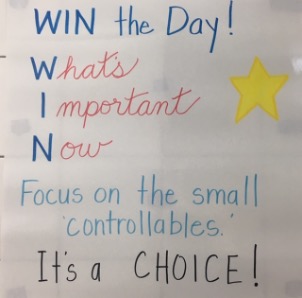

While at the conference, Jerry Lynch spoke for several sessions about the importance of identifying team core values to help intentionally develop character on sports teams. He gave the coaches an opportunity to reflect on 20 core values he thinks are important. Each coach whittled that list down to 10 after the first day. Then in the next session, coaches spent time choosing the four most important values to them as it relates to the role of a coach and leader of a group of student athletes. Lynch then gave a framework of how to implement this with their teams and get their athletes’ input on what was important to them. Here is our swim team’s story.

At the first team meeting of the season, Coach Cori Lee introduced the 10 core values she thinks were important for her team’s success this year. Then in age group divisions, they spent 20 minutes deciding which one of the values most resonated with them. The dialogue was intriguing because each group had to come to a consensus on just one core value to share with the rest of the team. It was also interesting to see what different age groups valued most. Though most groups had overlapping core values on their top three lists, none of the age groups had the same core value as their top choice. When this was all said and done, Coach Lee combined the team’s values with her own to land on six core values the team would focus on this season.

At daily swim practices, Coach Lee wove each of these values into her talks and conversations with the team. Each week one core value was chosen as a focus for the team. At the beginning of the week, Coach Lee would lead a brief dialogue around how the value applies individually, as a team and specifically to swimming. Later in the week, the HS swimmers shared a quote they selected that connects with that week’s value and how they live the core value as a swimmer. Team captains led the way and also shared personal stories from their own training to illustrate the value and importance of living the team’s values.

Coach Lee also created posters to hang on the pool deck and locker rooms throughout the season. Core values were also embedded into each of her email communications highlighting specific examples of ways the team was living out their core values.

One striking example came from a long time member of the team (and captain) who thought the idea of a Love Box would help the team to create strong bonds between them. She made a simple box where swimmers could drop a note into about a fellow teammate. Each week the kids would open the box and team captains would share aloud or deliver the messages. Imagine the feelings of the students when a positive and caring message was read about them. Think about the impact on those swimmers who wrote the notes, knowing they made someone else on their team feel special.

Coach Lee was able to use these core values when having a conversation with a group of swimmers who were having some social distractions on the team. They were able to revisit the values each of them agreed to and compare that with the behaviours they were exhibiting in the middle of the season. This was a very powerful tool to help them talk through and make changes to their behaviours and improve the relationships between them.

During the end of season SAISA swim meet held at The Lincoln School, Kathmandu, Nepal, Coach Lee displayed the Core Values in all of the team areas as well as on spirit bag tags for each swimmer. This helped the athletes to focus on things they could control throughout the swim meet and work to do their best at each event. Through the hard work of the swimmers and coaches, the team was honoured to take the first place team trophy and many members swam personal bests at the meet.

Here are a few responses from the swimmers when asked about their team’s core values.

How did the core values shape you as a teammate?

- It showed me things I should focus on to help contribute to the team. When we came up with it I knew it would be really impactful.

- As a teammate it made me more excited and motivated to train as hard as I could because everyone else lived by these core values.

- They helped me to remember what was important and why I was doing it. It also taught me to show love and commitment towards my teammates and coaches.

- It brought out the “togetherness” and joy for the sport. It made me both a better swimmer and a better teammate altogether.

How did the core values play a role in your swim training and your performance levels at the SAISA meet?

- It made me feel so much joy. 100 percent joy. Because not only did the perseverance and competitive part help but it felt like I was part of a family and that was what made me swim my hardest and try to win the title for my family.

- Personally, some of the team core values that we focused on were already strongly implemented within my swimming and day to day life like Competitive, Integrity, Commitment, and Perseverance. However, with the values of Love and Joyfulness, it was a reminder for me to also be able in swimming (especially at conferences) to take a step back and remember why I am swimming and who I get to swim with. I thought that each of our core values was significant in helping each swimmer do their best in the pool and be the best teammate.

- I was able to realize that it wasn’t about winning, it was about persevering, being committed, having integrity, being competitive, showing love and being joyful. This helped me to be less nervous because I knew that people would be proud of me whether I won or lost.

- Exclusively performance-wise, I don’t think they made me drop time, but they helped me experience SAISA in a much more positive way. I wasn’t only focused on winning a dropping time anymore, but on being there for my teammates, supporting them. This positive mindset helped me be less anxious about competing and satisfying my own expectations, which, now that I think about it, could have made me more relaxed and perform better.

What will you remember most about the work you did with your swim team core values that year?

- I’d say the aspect in which we all fully dedicated and put the core values to heart. We all persevered “when the going got tough”, we all were very committed to the sport and team, we all maintained integrity when or when not we were supervised, we were very competitive and loved that aspect to swimming, we loved the sport, each other, and became a family through it all, and finally, we enjoyed it. We enjoyed the time we had together and enjoyed working and getting through things together. Swimming brought us close and I will never forget the family that originated from such a simple sport — swimming.

- That year really solidified some of the realisations I’d been having about swimming for a long time. Over the years I realised that competing and performing well was not the most important part of swimming. Although it crushed my childhood hopes of taking the sport to a higher level, I realised that the most valuable experience was not winning or dropping time, but rather the connection that we had as a team. Nearly all of my closest friends I’ve met directly or indirectly through swimming, and I will always be grateful to Coach Lee for offering this new perspective on the sport, which places more emphasis on things like joy, compassion, and love, instead of competitiveness.

What do you think about the points raised in this article? We’d love to have your thoughts below.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Luther Rauk is currently a Middle School PE Teacher and coach at The American International School of Muscat, Oman. Originally from Minnesota, USA, Luther has also lived and taught in Thailand and Bahrain. Luther spent four years as the Athletic Director at TAISM where he developed a passion for learning how best to help coaches do their important work with kids. A desire to make real connections with students again led him to return to the PE classroom in 2018. To connect with Luther please follow him on Facebook, twitter@lutherrauk or email him at raukl@taism.com.